A Guide to Fragging. Part 2: Mushrooms

Author: Richard Aspinall

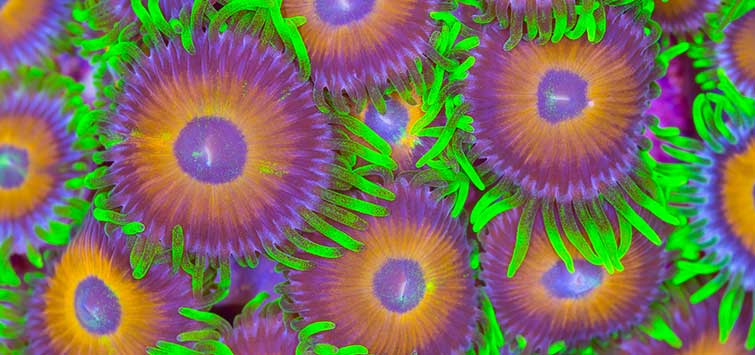

In Part 1 of my series on fragging, I touched on some of the benefits of the captive coral propagation process and how it can increase the number and types of corals you keep in your aquarium via swapping with fellow aquarists and selling coral frags. I wrote about fragging zoanthids and how it has become a distinct passion for many aquarists who find it a great way to support and expand their hobbies.

In this piece, I’ll focus on fragging corallimorphs—commonly called mushroom corals—but I want to offer a little advice about their growth and nature beforehand. In recent years the interest in mushroom polyps has waned a little, though not in the related Ricordea species.

Finding a Place for Mushroom Corals

In the early days of the hobby, these hardy animals were commonplace and could be seen covering the rockwork of many an aquarium. However, with the advent of higher-output lighting, increasingly efficient filtration systems, and greater understanding of water chemistry, many hobbyists have “moved beyond” mushroom polyps and, in some cases, regard them as a nuisance to be kept out of aquariums that are maintained and managed for small-polyped stony corals.

I still think mushroom corals have their place, as they are ideal for novice hobbyists and can be found in a wonderful array of colors and textures. In recent years, interest has turned to Ricordea yuma, a species from the Pacific Ocean that is similar to, yet unlike, the common Caribbean species R. florida.

Tendency to Spread

With the proper conditions, mushroom corals can grow very well, often to the point of dominating an aquarium. Like any other organism following a growth pattern that involves covering the substrate, mushroom corals can potentially encroach on other organisms. This habit of spreading works very well for us aquarists in the main, as it means we can provide an organism with bare rock and, after a period of time, the rock becomes a colorful and attractive feature.

We need to understand, though, that as time passes rockwork can become dominated by species that find the aquarium’s conditions particularly favorable. Mushroom corals can be exemplars of that tendency, and given that mushroom corals possess stinging nematocysts along their discs, their spread can become risky to other sessile organisms.

Mushroom corals are able to cover rocks through a series of related methods and mechanisms. As one animal moves across a substrate it can leave pieces of its pedal disc on the rock; those pieces then grow into new specimens. Another method relies on the mushroom coral’s ability—as the number of individuals increases—to separate across their column and allow the aquarium’s flow to move the newly separated oral disc until it settles down in a suitable location, thus beginning the cycle again.

Aquarists may also note that mushroom corals divide in half in the same manner as anemones. The abilities of these corals to spread and prosper, after what would appear to us more “complicated” animals as a catastrophic series of events, is what we seek to work with in order to frag them and exploit the gifts evolution has provided.

Managing Mushroom Populations

I have a small number of mushroom polyps, which are limited to certain areas of the tank that receive less light than others. This works very well for me, as I prefer to concentrate on my SPS colonies, but another way that works equally well and limits overgrowth is to isolate mushrooms—and other corallimorphs with the same tendency—to solitary “islands” of rockwork, thus limiting their chances of moving to adjacent rockwork and decorations, as they tend to avoid attaching to sand.

This works to a degree, but should you wish to avoid those approaches entirely you will need to keep a watch for polyps that detach and remove them if you can. If they do settle, you may want to physically remove them before they increase in size and number. Removal can be achieved through literally brushing them into goo with a firm-bristled tool, but you have to try to remove as much of the tissue as possible with a siphon as you go.

Mushroom Coral Toxins

It’s not just that the resulting matter will cause a nutrient spike; the dying creature also will release toxins into the water that can irritate and stress other inhabitants of the tank. Needless to say, don’t undertake a mass eradication in one go. If possible, take the rock out of the system entirely to remove the unwanted mushroom.

Unclear Effects

The effect of chemicals produced by mushroom corals is not entirely understood, although experts on the subject do note that many aquarists find that corals adjacent to mushrooms rarely thrive. It is wise to keep up with replacing activated carbon and to use powerful skimmers to remove potentially damaging chemicals that may impact upon the health of other species, from corals to fish.

Preventing Dangerous Chemicals

In this instance using a carbon reactor and mechanical filtration, which removes tiny particles, may be imperative to prevent serious problems within your tank. Also, remember to change your mechanical filtration socks after eradicating the unwanted corals.

The best course of action is limiting their growth in the first place, and this is where keeping your nutrients down as far as possible will help. Mushrooms, although they do possess a gut, lack the feeding tentacles we associate with more typical corals and appear to derive the bulk of their nutrition from the water around them along with their onboard zooxanthellae. They are able to feed, but it appears that they feed on items that have settled on the disc instead of having been caught by the coral.

However, should you wish to develop an area of your tank, or a separate tank particularly suited to mushroom corals, then the general advice in literature suggests providing lower-intensity lighting and moderate levels of flow, quite unlike the conditions found in SPS- or LPS-dedicated reef aquariums.

How to Frag Mushroom Corals

In fragging mushroom corals, we exploit their natural ability to survive and prosper from physical damage, and we will be taking a knife to them in a life-threatening manner—but fear not, these corals can take it. I should also add that in my research for this article I have not found anything to indicate that the chemicals and tissues contained within mushroom corals are hazardous to human health, but you might want to wear latex gloves and facial protection if you want to be extra careful.

Step 1

The first thing you need to do is to set up your work station. A well-lit table or desk that you can get wet without upsetting the rest of your household is ideal.

I use a small chopping board and tend to hold the animals in a shallow bath of aquarium water. You can use a range of containers for this purpose, but make sure they are classed as food-safe and are well cleaned and free of domestic chemicals. Once you have your work area set up you can select the individual specimens you wish to propagate. Ideally they should be as large as possible to provide lots of material to work with. This process can be fiddly!

Step 2

Once you have your intended specimen identified, the fun can begin. First, you need to separate it from the rock it is attached to. It will no doubt shrink quite a bit, but you should be able to see the much-reduced disc atop a narrower column. You will need a very sharp knife; I prefer the craft knives with curved blades for this process, but a straight-edged blade will suffice. I find the curved ones easier to generate a clean downward cut, but that’s just my preference. Simply cut the coral across the column, leaving the attachment disc behind.

As you do this you will notice a huge amount of mucus generated and also the white filaments of the animal’s gut; this can all be discarded to leave the quartered disc behind. In fact it’s a good idea to rinse the frags to remove the “goo” before placing them into another holding bath of aquarium water.

Step 3

The mushrooms’ ability to regenerate from small pieces of tissue now comes in very handy. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the frags grow better when a small piece of the central oral cavity is left in each resulting frag, so as you cut the disc into pieces (with my clumsy hands the best I can do is to cut them into four pieces, like quartering a pie), use the oral cavity as a starting point for each cut and leave some of this tissue behind in each segment.

Step 4

Because of the large amount of slime these animals produce, you cannot rely on cyanoacrylate glue to attach them to another piece of rock or specially designed fragging disc. The best way that I have found is to fill a shallow container with small pieces of live rock rubble and aquarium water and place the frags gently onto the small rocks. If you can then cover the container with fine mesh held in place with an elastic band to stop the frags from washing away into the tank, all the better—you might try using some cyanoacrylate to hold them in place, but this is likely to be a temporary solution. Covering the corals also keeps out fish and hermit crabs that may disturb the frags.

Step 5

In an ideal situation you will be able to return the container with its cargo of frags back to a low-current, low-light area of your aquarium, sump, or fragging tank without causing the frags to move unduly (because of the mesh), although they may become shifted a little. Don’t be too concerned about this, as they will right themselves as they grow and attach. It will take several days for them to heal and a few weeks before they have become smaller copies of the parent. At this point you can take them, attached to small pieces of live rock, from the container and attach those small rocks to larger pieces to build up a new colony.

Final Thoughts

It’s worth noting that many reef aquarists have established frag tanks for the sole purpose of housing newly cut fragments or allowing various frags to grow. These tanks have grown in popularity, to the point that many aquarium companies are offering all-in-one frag tanks that are often shallow to allow light penetration.

If you intend to frag corals on a regular basis, it may be worthwhile to invest in a separate frag tank. By selling coral fragments, you could easily pay for the entire setup.

And that’s it. The process is very straightforward, but I’d like to emphasize that you should keep up with replacing your activated carbon while maintaining skimming and water changes to limit any impacts upon your other tank inhabitants.

.png?h=595&iar=0&w=2781&hash=5FD5E69473BCC22199FBFA2FB71B6033)