Sepia bandensis Husbandry and Breeding

Author: Richard Ross

An alien-like look, color-changing ability, and fascinating predatory behaviors make this cuttlefish an incredible choice for marine aquaria, but its short lifespan is discouraging to some. A cephalopod enthusiast and breeder lays out the husbandry essentials, as well as what to provide the young.

Fascinating Dwarf Cuttlefish

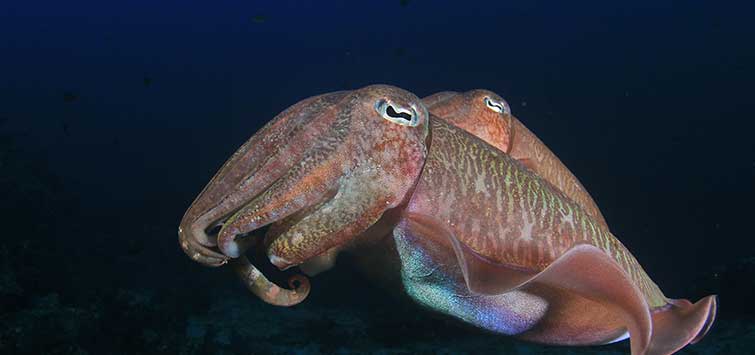

The dwarf cuttlefish Sepia bandensis is one of the coolest animals on the planet. It zips through the water like a little UFO, able to instantly change direction and speed. As it darts around the tank, it can change the color and texture of its skin—going from static rock-like camouflage to patterns flowing across the canvas of its skin in an instant. Sepia bandensis is a phenomenal predator, patiently stalking a potential meal before shooting its two feeding tentacles forward, like a lizard’s tongue, to snatch its prey.

It will even come to the front of the tank to greet you when you walk into the room (although it may just recognize that you are the source of food). Best of all, it won’t try to climb out of the tank like its eight-armed octopus cousins. All in all, it is one of the most fascinating animals I have ever had the opportunity to keep in aquaria.

Wild Specimens

Wild-collected adult Sepia bandensis ship poorly, with high mortality rates, and because they are adults, they may only have months or weeks left to live when they finally arrive at your home. However, in the last few years, alternatives to wild-caught adults have presented themselves.

Wild-caught eggs appear on the market with regularity, and our understanding of how to raise the eggs and hatchlings has advanced greatly. Even more exciting is the success people have had captive-breeding Sepia bandensis, and captive-bred eggs and hatchling cuttles are offered for sale by breeders with increasing regularity. This means that not only is nothing taken from the wild, but the availability of Sepia bandensis is no longer dependant on the seasonal availability of wild animals.

Cuttlefish Basics

Sepia bandensis is a cephalopod, related to the octopus, squid, and nautilus. S. bandensis have eight arms, two feeding tentacles, three hearts, a ring-shaped brain, a cuttle bone that helps control buoyancy, a fin that girds their mantle for fine maneuvering, a funnel that gives them jet-like propulsion, superb 360-degree vision (though it appears they are color blind), copper-based blood, and the ability to squirt ink.

They mate readily at around five months old and lay clusters of ink-covered eggs that resemble bunches of grapes. When the hatchlings are born they are tiny and measure less than ¼ inch long, but they can grow to an inch long within two months and to about 4 inches within six months.

An Awful Truth

Dwarf cuttlefish only live about a year. What makes this short lifespan even worse is how many cephalopods die: They go into what is called senescence. During senescence, the cephalopod essentially wastes away. They become listless and their eyesight and coordination start to fail, causing them to have difficulty hunting or even accepting food placed directly into their arms. Sometimes their arms and body will begin to rot in place. I have seen hermit crabs feeding off still-living Sepia bandensis while the cuttlefish does nothing, showing no signs that it is even aware of what is happening.

In the wild, a cuttlefish going through senescence doesn’t last long, as it is quickly eaten by other animals. In captivity, however, with careful feeding by the aquarist, it is possible for such a cuttlefish to linger for months while slowly declining. I bring this up because it is important to be ready for this aspect of keeping a cuttlefish, and to drive home the point that captive breeding of these animals is important. If you captive breed them, it seems to somehow make the short life of the animal feel less tragic and more meaningful.

General Husbandry

The basic requirements for Sepia bandensis husbandry are roughly the same as for corals—clean, stable water conditions that simulate natural seawater conditions. I suggest live rock for biological filtration, ammonia and nitrite levels of zero, and nitrate levels as low as possible. Salinity should be near 34.5, temperature around 78°F, and pH should be between 8.0 and 8.5.

Skimming

A skimmer is a must, not only for the oxygen it puts into the water and the waste it skims out of the tank, but because it also does a great job of removing any cephalopod ink from the water before it has a chance to do any damage to the animals. With the amount of waste these predators create from unconsumed food, adding a phosphate reactor with phosphate adsorbing media may also be a good idea. Finally, if nitrates become a problem, a sulfur denitrator or remote deep sand bed for natural nitrate reduction can be added.

Tank Size

A single Sepia bandensis can live well in a 30-gallon aquarium, and many of the all-in-one aquariums on the market right now can work very well as cuttlefish tanks. For two Sepia bandensis, I don’t recommend anything smaller than 40 gallons, and three Sepia bandensis should do well in a 55. I have also kept groups of eight in 125-gallon tanks. Groups of Sepia bandensis can be kept together as long as they are kept fed and provided enough space. Without adequate space and food, the cuttlefish will fight and possibly damage or even eat each other.

Lighting

Sepia bandensis have no specific lighting requirements and will thrive under simple fluorescent lights or more powerful metal halide lighting. Similarly, Sepia bandensis will thrive under different levels of water flow, but I suggest you err on the side of more flow rather than less.

Aquascaping

The aquascaping for a cuttlefish tank is mostly up to the personal preference of the aquarist, as cuttles can flourish in a wide variety of setups. Some caves or overhangs should be provided for them to hide in. Growing macroalgae can also be used as nice hiding places for cuttles to hang out, and they can also uptake excess nutrients in the water. An inch or so of sand is also a nice addition because cuttles may bury themselves in sand, but their digging may be detrimental to deeper sand beds.

Feeding

Cuttlefish can be messy eaters that drop uneaten food all over the tank, and it is important to get that food out before water quality deteriorates. Hermit crabs and snails are safe from predation by cuttlefish and can help with uneaten food. In my opinion, bristleworms make great tank janitors for cuttlefish because they breed readily and quickly consume dropped food.

No Fish Tankmates!

Fish as tankmates should be avoided. If we follow up most stories of cephalopods being kept successfully with fish, we find that the success only lasts a few months before the fish eats the cephalopod or the other way around. Corals, on the other hand, make great tankmates for cuttlefish as long as they are not the stinging variety. There is at least one Sepia bandensis breeder that has had great success breeding them in a full-blown reef tank with bright metal halide lighting and massive flow.

Nursery for Small Cuttles

Sepia bandensis start off small and get larger quickly, which means their food and space requirements change as they grow. While it’s easy to say two Sepia bandensis can live comfortably in a 40-gallon tank, the reality of the situation is that you probably don’t want to put two hatchling cuttlefish in a tank this size—you will never see them or be able to know if they are eating. Hatchling cuttles are only ¼ inch long and can be completely lost in a larger tank, making it impossible to even know if they are feeding.

An easy way to deal with this aspect of Sepia bandensis husbandry is to keep hatchlings in some sort of nursery such as a commercially available net breeder, which is often used for livebearing fish. When setting up the net, I suggest turning it inside out so the hatchlings don’t get caught up in the extra netting at the seams. Hang-on tank refugiums can also be used, as well as small nursery aquariums plumbed into the system—although you must take precautions to ensure the hatchlings won’t be washed out of the container by water returning to the tank, such as using a foam filter sponge over the outflow.

I like net breeders because they are simple, inexpensive, and incredibly easy to set up. The net breeders hang on the inside of the aquarium and allow water to flow freely through the net, so no extra filtration or plumbing is needed. You can easily look through the top to keep track of the health and growth of the cuttles. I have successfully kept four hatchling Sepia bandensis in net breeders for the first two to three months of their lives, and once they grow to about an inch in length, they can be let loose in the larger tank.

Feeding Young Cuttles

Net breeders are also great because they keep hatchling cuttlefish in close proximity to their food. For at least the first two weeks after hatching, Sepia bandensis will need some sort of live food, and keeping the food closer to the hatchlings makes it more likely they will be able to find and eat it. The more they eat, the faster they will grow, and the sooner you can release them into their permanent home.

Mysis Shrimp

By far, the most successful food for hatchling Sepia bandensis is live mysis shrimp. Mysis are highly nutritious and relatively easy for the hatchlings to catch. I prefer cultured mysis to wild mysis because, in my experience, they have better survival rates, but plenty of other cephalopod keepers have had great success with wild mysis.

Avoid Brine Shrimp

It is important to note that live brine shrimp, though readily available and inexpensive, are widely considered terrible food for cephalopods. Cephalopods raised on live brine, even enriched live brine, have low survival rates and short lives.

Preserving Food

Keeping any live food alive can be challenging, and the challenge is compounded with mysis because they can be cannibalistic. To reduce this potential issue, avoid overcrowding and be sure to feed rotifers or other suitable foods regularly. Net breeders can be utilized, or another small tank can be set up to keep the mysis until they are ready to be fed to the cuttlefish. It’s also important to get a feel for how many mysis you need per week and order them before you run out, so your cuttlefish don’t starve or eat each other!

Amphipods

If you are lucky enough to live near the ocean, you may be able to collect your own hatchling cuttle food in the form of small amphipods. Make sure to collect from waters that are as unpolluted as possible, and make sure to check with local regulations regarding collection before beginning. Amphipods can be much more robust than mysis and escape from hatchling cuttlefish more easily. I recommend you start with mysis for the first week or so, allowing your baby cuttlefish to learn hunting skills with the easier prey.

Hatchlings should be fed several times a day and only as much as they catch in a few minutes. I recommend avoiding flood-feeding of live food; with so many food organisms in the tank, not only can hatchling Sepia bandensis stop seeing them as prey items, but such abundance can make the hatchlings harder to wean onto non-living food.

Weaning Cuttlefish

Since live food can be expensive, it’s great to wean your cuttlefish onto thawed frozen food as soon as possible—frozen mysis are a good choice for size and nutrition. Since cuttlefish rely on their eyesight to hunt, often the non-living food items may need to be moving to get the cuttlefish to strike. Start by introducing thawed mysis with your live food.

The hatchlings, conditioned to strike when live food is dropped into their breeder net, will usually snap up the dead mysis as well. Sometimes you will have to make the non-living prey look alive by gently blowing it around, just barely moving it, with a small pipette or turkey baster. Weaning onto non-living foods may not work until the hatchlings have moved off small prey and onto larger prey, and determining when your hatchlings are able to move off smaller food is a judgment call.

Switching to Larger Food

When your cuttlefish are a month old and have had time to hone their hunting skill on weaker, smaller food, you can try feeding them larger food—even up to foods the same size as the cuttlefish. Shore shrimp or marine janitors can be ordered online in various different sizes, and they make a great food for cuttlefish. Just like mysis, they need to be kept alive until fed to the cuttlefish, so be prepared. Once the cuttlefish are taking larger prey, the weaning process described above works quickly and effectively, but instead of using non-living mysis, you need to use non-living, freshly killed, or thawed frozen shrimp.

Feeding Stations

Another weaning method that cephalopod enthusiasts have been experimenting with is some kind of shrimp hanger or feeding station. Glue or tie a small rock to a piece of fishing line as a sinker. Tie the other end, or secure the other end, above the tank so the sinker will be a couple of inches above the bottom of the tank. In the middle of the line, tie or glue a plastic toothpick and skewer a dead shrimp onto it. When you place this device into the tank, the current should make the shrimp on the toothpick move around, which will help attract the cuttlefish to feed. If you have multiple cuttlefish, add more toothpicks to the line for more shrimp.

Feeding Options

Weaned or not, as the cuttlefish get bigger you will need to get them larger food items. Again, if you live near the ocean, you can collect local crabs or shrimp as needed. You can also check with local bait shops, which may have live shrimp ready to sell. If you live away from the ocean, you can order live fiddler crabs or appropriately sized shrimp from online vendors. If you have weaned your cuttles onto thawed frozen food, any live food, bought or collected, can be obtained in bulk and frozen to use when needed. Frozen bait shrimp or prawns can also be bought or ordered, and even raw, unshelled, and unflavored shrimp from the grocery store can be used.

It is important to note that freshwater feeder fish are not a suitable food source for cuttlefish. Not only do they lack fatty acids of saltwater animals, but they are often treated with copper, which is deadly to cephalopods. There is no real consensus among cephalopod enthusiasts regarding the suitability of using freshwater crustaceans, like ghost shrimp, as food for saltwater animals, so I would suggest limiting their use as cuttlefish food.

Breeding

Even though cuttlefish can tell each other’s sex on sight, it is very difficult for us to accurately sex them if they aren’t actually seen mating. In general, Sepia bandensis males tend to adopt high-contrast black-and-white patterns when faced with another male, while females tend to keep the more relaxed mottled colors that a resting cuttlefish adopts. However, males sometimes display like females and females sometimes display like males, so to be really sure, you need to see them mating.

Mating Ritual

Cuttlefish mate by coupling head to head. In this position, the male deposits a packet of sperm called a spermatophore into a pouch in the female’s mantle. The mating can last from 10 seconds to many minutes, and it appears that males can use their funnel to flush other males’ sperm out of the female’s pouch. Females can lay several clutches of eggs, up to 250 and can live for months after the first egglaying.

Mating begins around the fifth month, while male displays begin around the third. It is unclear how long it takes from mating to egglaying.

In groups, Sepia bandensis will mate readily. Males will know when a female is receptive to mating and will start to display towards each other with the black-and-white patterns mentioned above, as well as stretch out their arms to intimidate their rivals. The male that wins then mates with the female. Oddly enough, sometimes when several males are displaying towards each other, another male will mate with the female while the other males are occupied with each other. It is also possible for mating to occur with no preamble—the male just swims up to the female, grabs her, and mates.

Eggs

After a successful mating, the female will choose a place to lay eggs. She might lay her eggs on a rock, on the side of the tank, on some macroalgae, or on tubing. I have had females lay eggs directly on powerheads or eggcrate tank dividers. The eggs are laid one at a time and will form a cluster that looks like a bunch of rubbery grapes. In Sepia bandensis, the female adds a little bit of ink to each egg, giving them the reddish/black color.

Hatching the Eggs

Healthy eggs will start off with a slight point on the end and slowly expand over three to four weeks, becoming thinner and more transparent, so much so that it becomes possible to see the baby cuttlefish while it is still in the egg. As the baby matures in the egg, the yolk sack, attached at the front of the cuttle where the arms are/will be, shrinks and then finally disappears. The cuttle will even start to swim inside of the egg just prior to hatching.

Fertility of eggs can range from high to low. I have had entire clusters that have frustratingly failed to develop. It is also possible for hatchlings to emerge from the egg with a yolk sac still attached. This is probably caused by some stressor, and these premature hatchlings rarely, if ever, survive longer than a week.

Assuming you have healthy eggs, I suggest leaving them in place until you start to see the yolk sac disappear. I like to use a small pair of scissors to snip the material that holds the eggs to where they have been laid, taking care to cut as far away from the egg as possible. Be gentle; the eggs can be quite fragile, and it is easy to accidentally puncture or break the egg. Usually the cluster is held in place only at one or two points, so removal is not that difficult. Once the cluster is free, use a cup with tank water, not a net, to move the eggs to their nursery area or net breeder, and then leave them alone until they hatch.

Raising the Hatchlings

It is common for hatchlings not to eat the first few days after hatching, so after a few days you can start to offer them their first live foods and be well on your way to continuing your population of Sepia bandensis.

When you’ve successfully bred your Sepia bandensis, it’s time to trade brood stock with other successful breeders. By doing this conscientiously, we can avoid inbreeding and the potential fecundity drop-off that often accompanies the captive breeding of cephalopods.

A Rewarding Challenge

I have found keeping and breeding Sepia bandensis to be fulfilling and rewarding, and I look forward to more and more people having success with these amazing little creatures.

References & Resources

Daisy Hill Cuttle Farm: www.daisyhillcephfarm.com

Dunlop, Colin, and Nancy King. 2009. Cephalopods: Octopuses and Cuttlefish for the Home Aquarium. T.F.H Publications. Neptune City, NJ. 239 pp.

The Octopus News Magazine Online: www.tonmo.com

TFH Digital URL: http://www.tfhdigital.com/tfh/200908/#pg105

.png?h=595&iar=0&w=2781&hash=5FD5E69473BCC22199FBFA2FB71B6033)