The Skeptical Fishkeeper: Compatibility

Author: Laura Muha

The Skeptical Fishkeeper: June 2007

When I left off at the end of last month’s column, I’d just purchased my dream tank: a 125 gallon that, theoretically at least, was large enough to house the assorted occupants of my various smaller tropical freshwater tanks. I’d also concluded that the species I wanted to put in it would be able to handle the same water parameters, even though those parameters weren’t necessarily those of their native habitats.

But water parameters aren’t the only things an aquarist has to consider when calculating the likelihood that a group of fish will successfully cohabitate, whether in a community display tank, a quarantine tank, or a short-term holding tank. As most of us who’ve shared quarters with another human being already know, the habits and behavior of the parties involved have the potential to wreak havoc on living arrangements, or at least to make them a lot more stressful. And in that regard, fish aren’t any different than us humans.

Choosing Compatible Fish

Although most of the species I wanted to put into my new setup had long-standing reputations as peaceful community fish—among them pearl gouramis, platys, rainbowfish, emerald catfish, and rosy barbs—the wildcard was my burgeoning colony of Neolamprologus multifasciatus, a shell-dwelling African cichlid. They’re hardly the most aggressive of cichlids, but they definitely are protective of their territory. It’s not unusual to find them in Tanganyikan tanks where the other occupants are aggressive enough to hold their own, but they’re not a typical choice for a non-cichlid community tank. The only reason I was hoping to include them in mine was because I’d wound up with more aquariums than I had time to care for, but didn’t want to give away any of my fish, some of which were holdovers from my first aquarium and were in their twilight years. Once they aged out I planned to convert the 125 to a Tanganyikan setup that included the multis, but in the meantime I wanted to cut my workload by putting non-cichlids in with them. The question was whether everyone could peacefully co-exist.

Looking for answers, I called Ray Lucas, a nationally known hobbyist from Boston, New York, who lectures on fishkeeping issues at clubs across the country. His suggestion: “Think of the world of the community tank as the city of Buffalo, the city of New York, the city of Los Angeles.” Those cities are inhabited by lots of different people from lots of different backgrounds and cultures living in close proximity to one another, he pointed out. Yet they generally get along without too much squabbling thanks to the existence of laws and (unfortunately to a lesser degree) society’s code of manners, which encourage them to respect one another’s space.

Why Some Fish Don’t Get Along

In a fish tank, obviously, neither laws nor manners will go very far toward keeping inter-species peace, but there are still lessons to be learned from the city analogy. Lucas pointed out that when conflicts occur among humans, it’s usually because one group feels another is infringing upon the resources it needs for survival, such as housing, food, or employment. And that often occurs because there isn’t enough of the resource in question to go around. The same (minus employment) can be said of fish.

So the bottom-line question I had to ask myself when deciding whether to proceed with my unusual community setup was whether I, as the keeper, could supply enough of what each species needed to keep it from trying to wrest it from another, Lucas said.

How Aquascaping Helps

If I’d been stocking the tank from scratch, that would have meant researching the needs of various species. (“I can’t stress that enough,” Lucas said. “Do your homework!”) But since I had been keeping all the fish I was planning to put in the tank for a number of years, I already was quite familiar with their needs and habits, and could move on to the next step: thinking through the areas in which they might clash with one another and making sure I could create a habitat that would mitigate that.

For instance, had I been stocking a 10-gallon tank I could have put a fairly large colony of multis into it because they don’t mind setting up housekeeping quite literally on top of one another in heaps of shells and rocks. I might also have been able to get away with putting a couple of other small fish in with them as long as those fish were mid-water or surface dwellers that wouldn’t compete with the multis for the same square footage at the bottom of the tank. But had I put emerald catfish and multis into the same small space I almost certainly would have had problems, because they would have had to battle one another for the same chunk of real estate. The result? Stress for both species and, most likely, a poor outcome.

Fortunately, however, I wasn’t stocking a 10-gallon tank; I was stocking a 125, which is 6 feet long. That would allow me to set aside 18 to 24 inches of tank bottom at one end of the tank for the Tanganyikans, and the rest for the catfish and rosy barbs, which like to spend a lot of time rooting in the gravel. By aquascaping the Tanganyikan end of the tank with the sand, rocks, and shells that appeal to the multis, and the rest with small, smooth gravel and driftwood that would appeal to everyone else, I could encourage everyone to stay in their own areas without setting up formal tank dividers.

Such a big tank also gave me the ability to provide for the needs of the mid-water and surface dwellers, too, with a large swath of open water at the front of the tank for the fast-swimming rainbowfish, and an area of still water between the overflow boxes for the surface-dwelling gouramis. I could also add lots of silk plants and driftwood toward the back of the tank to provide hiding places for fish that were feeling the need to get away from it all. In other words, the answer to the question of whether I could aquascape my tank to meet the needs of each group of fish was a definite yes.

Every Fish Is Different

But I also knew I couldn’t afford to forget that fish are living beings, and like most living beings they have individual quirks. That means that no matter how much research you do into a species, and no matter how carefully you set up your tank, you have to be prepared to venture into the somewhat-less-than-scientific area of fish psychology.

Once again, however, I was at an advantage because I’d been observing the fish in my tanks for several years. So I knew, for example, that one of my male rainbowfish was unusually aggressive toward another member of the group, whom he clearly felt was threatening his dominance. While male rainbowfish do typically spend a lot of time squabbling over their places in the group hierarchy, this rarely involves anything more than posturing, with the fish hovering flank to flank while rapidly fanning their fins and glaring at one another. However, in the case of my fish, one had persecuted the other so mercilessly that it cowered in the back, afraid to come out even to eat. Eventually, I’d separated them.

The Impact of Tank Layout

But now, a couple of years had passed and I wanted to try keeping them in the same tank again, and I had a couple of tools at my disposal that might encourage a better outcome this time. First, I could transfer the more subservient male into the new tank first, so he’d begin to think of it as his territory. That might encourage him to stand up to the bully, who at the same time would feel he was coming into someone else’s space and behave a little more civilly.

Had I been moving the less dominant fish back into the tank of the dominant fish, I also could have tried shuffling the plants, driftwood, and other decor in the tank first, encouraging the dominant fish to think he was in a new environment and evening out the playing field.

And, as a side note, I also suspect that making major changes in the decor of the room in which the tank is housed sometimes can have a similar effect on sensitive fish. A couple of years ago, I gently slid one tank a dozen feet across the room and, although not so much as a piece of gravel inside the tank was disturbed, a trio of gouramis that had been living in peace for well over a year almost immediately launched into a hierarchical struggle which took several days to settle down—something that made sense considering that the view beyond the tank walls must seem to the fish to be a part of their extended environment; when it changed, they may well have felt that their overall environment had changed as well.

Transferring Fish Between Tanks

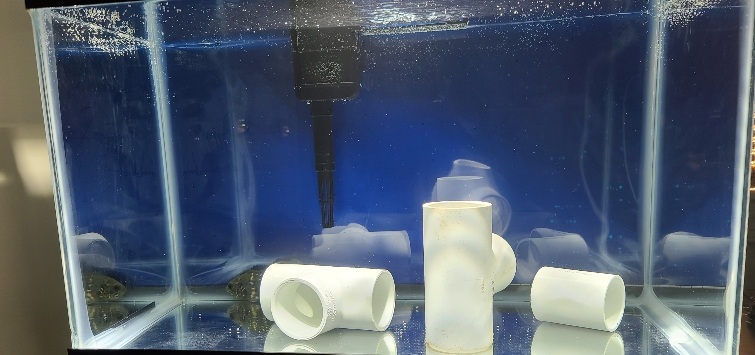

When it was time to transfer the fish, I started with the shell-dwellers so they could establish their colony before anyone else arrived. Multis dart into their shells the minute you stick your hand in the tank, so they aren’t hard to move; assuming water conditions in the new tank are similar, you can simply pick up the shell and transfer it. I set each shell down within the “Tanganyikan territory,” and was delighted to see that within a couple of hours the little fish were already busy setting up housekeeping. A couple of them did venture beyond the “Tanganyikan territory” to take up residence under the driftwood toward the center of the tank, but not so far from it that I thought they’d distress the rest of the fish, which I then began to move into the tank. (I also transferred all the filter material from my old tanks, so I wouldn’t have to worry about cycling.)

First came the platys, since they tend to be calm little fish, and I figured that if they were swimming around contentedly they’d reassure the more sensitive fish that the new tank was safe. Then came the pearl gouramis, emerald catfish, and the more subservient red Irian rainbowfish—followed by a hitch.

While the multis ignored the larger fish and busily went about their lives, the reverse wasn’t true—most of the larger fish were so alarmed by the shell-dwellers that they went into hiding, with even the normally unflappable platys wedging themselves behind rocks. Only the emerald catfish—which generally like to stay out of sight—seemed unperturbed and quickly took to perching on the rocks overlooking the multi colony, although I wasn’t sure whether that was because they were curious, thought they’d found kindred bottom-dwelling spirits, or simply thought they’d found a potential lunch source.

However, when I dropped a little food in the tank everyone did dart from hiding to snatch some, so I decided it was worth giving the fish a little time to get used to their new digs. And sure enough, within the week the larger fish began to venture forth.

At that point I added some of the rosy barbs and smaller rainbowfish and allowed them to settle in; I was pleased to see the more bashful red Irian male swim over and immediately let them know who was boss. After letting the fish settle in for another week, I took the plunge and moved the aggressive red Irian male, and I was dismayed to see the battling begin in earnest. The more bashful male did attempt to assert himself, but the more aggressive male refused to be cowed. They spent the rest of the day chasing one another around the tank, and by afternoon the gentler fish was hiding behind one of the filter outflow pipes. I sighed in frustration, figuring I was going to have to separate them once again, but by the next morning the two seemed to have achieved some kind of detente, because the gentler fish was back in the mix and the bolder fish let him stay there.

Peace Reigns

In the months since, peace has reigned in the tank. Multi fry are appearing with regularity; the gouramis are in breeding dress. Would I call my experiment a success?

So far, absolutely—although I continue to keep an eye on things, because as I’ve already said, fish are living beings, and like all living beings they don’t always act in predictable ways. And isn’t that one of the things that makes this hobby so interesting?

.png?h=595&iar=0&w=2781&hash=5FD5E69473BCC22199FBFA2FB71B6033)